Topics you should avoid

Topics you should avoid |

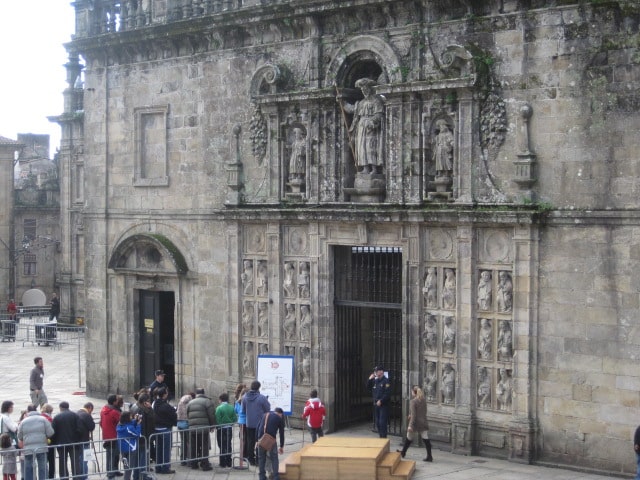

You’ve been dreaming for ages about walking the Camino. You’ve planned, packed, trained… and you’re finally in Spain. Of course, you want to make the most of this amazing experience and hope that the time spent in Spain will go as smoothly as possible.

That can include a wide range of things, such as your flights not being delayed, not suffering any injuries or ampollas (blisters) and making meaningful connections with both fellow peregrinos and locals.

Some of these things are beyond your control, so we’ll not discuss them now. Others, however, you have power over.

It’s surprising how different things can be in another country, even one that is in theory close to ours: you say or do something that is perfectly OK in your homeland, and all of a sudden you can sense the mood changing. For the worse.

So, what should you do?

In order to minimise potential problems or awkward situations with Spaniards, there are certain behaviours and topics you’d better avoid.

Don’t criticise

As mentioned in this previous post, avoid criticising our customs; whether it’s mealtimes, siesta, bullfighting or something else. We may privately agree with you. But the fact that you, a foreigner, just came into our country and “have the nerve” to tell us how we should be doing things will not be welcome.

I mean, you wouldn’t like it if we went to your country and told you how to run it, would you?

Topics you should avoid

You should tread carefully if discussing política (politics) and religión (religion). In fact, my advice would be to stay away from those 2 as much as possible.

Politics is maybe an obvious subject to avoid. People can be very passionate about their political ideas and things can easily get heated when we don’t agree.

And I’m not just talking about current affair issues like the latest election results or the independence of Cataluña (Catalonia). Other “older” topics like the Spanish Civil War can also be very touchy and nobody will appreciate you, a foreigner, sharing your thoughts about it and “coming to teach us lessons”. That’s how most Spaniards would see it and that’s also one of the most polite replies you will get. So, stay away from it.

Oh! And please don’t even suggest that the Catalan, Basque and Galician languages are dialects, especially if you are talking to someone from one of those regions! They ARE languages and, in fact, they are co-official with Spanish in their respective territories. It really upsets many of us when you call them dialects.

Religion, on the other hand, is considered a private matter in Spain. You don’t ask someone you just met about their religious beliefs or practices. Of course, some walk the Camino for religious reasons, but some others don’t. So, unless they bring it up, I would also stay away from it. You’re just going to make people uncomfortable if you ask.

Bursting stereotypes

While I’m on this topic, I’d like to clarify some common misconceptions people tend to have about Spain and religion.

- First of all, Spain has no official religion. After Franco’s dictatorship, Catholicism was abolished as the country’s official religion. Our current Constitution, adopted in 1978, establishes the right to religious freedom.

- Secondly, Spain is not a deeply Catholic country, at least not in the way many foreigners think it is. According to the latest surveys, 2 thirds of Spaniards consider themselves Catholic, but only 22% of them attend church on a regular basis. Almost 30% of Spaniards identify as atheist, agnostic or non-believers.

You should avoid this, too

Before we finish for today, let me give you one final tip:

Please, don’t tell us we have a lisp because of some king or another a few centuries ago!

It’s not true; actually, it’s quite a ludicrous theory and all it shows is that you don’t know what a lisp is.

A lisp is a speech disorder characterised by the inability to correctly pronounce the S sounds. People with a lisp typically pronounce S sounds as TH.

In Spain, there is a difference in pronunciation (and meaning) between the words seta (mushroom) and zeta (the letter z), or cocer (to boil) and coser (to sew), just to mention a couple of examples. Just the same way that an English speaker pronounces sink & think differently. So, if we have a lisp, I guess you do, too!

You’ve been warned. Now you know what topics you should avoid, so it’s up to you to stay out of trouble.

Today’s words

Ampolla

Peregrino

Política

Religión

Cataluña

cocer / coser

seta / zeta